Sasha leads Base UA’s cultural team on the ground. She originally comes from the City of Donetsk, which has been occupied by pro-Russian separatists since 2014

Sasha leads Base UA’s cultural team on the ground. She originally comes from the City of Donetsk, which has been occupied by pro-Russian separatists since 2014, when the war in Ukraine actually started. The 28-year-old lived in occupied Donetsk for about a year and a half – together with her mother. “But I understood that there was no future for me. It’s such a limited environment,” she says. “Most of the young people and also my friends fled Donetsk, so it was really hard to create a community and do something politically or culturally. It’s absolutely surreal.”

So she fled the country but came back to work for Base UA NGO.

How does it feel to be back in this environment? Why is it so important to work with kids on the ground? Sasha gives an insight into her cultural and social work in Donetsk region while there is a dehumanizing war going on.

Sasha, how did the idea to make cultural events in Donetsk region grow?

It started because the organization was already here in Donetsk Region doing so many things on the ground – and most of the team members have some sort of cultural or artistic background. It would be weird not to use these skills.

Why?

Because after more than one year of full-scale invasion, there are still so many children staying in Donetsk region. It totally makes sense to use our knowledge to do something for them. We found out that they still have only online school – for more than 3 years now because of the pandemic. There are no social activities, and no after-school activities at all. The understanding that their development is currently led in such an unhealthy way was the trigger to organize something.

And what was your personal trigger doing this kind of work?

I left Ukraine in 2018 and moved to the Czech Republic. I moved there to study theater. Before that I commuted between Kyiv and my hometown Donetsk. When the invasion began, I was very close to the end of my studies, and it totally disrupted my flow. So I started helping Ukrainians on the ground, finding accommodation, did translations and so on. Also, my university started this initiative “Students For Ukraine” and I was coordinating Ukrainian students who fled the country and organizing short term curriculum for them.

So you found your role in the Czech Republic – what made you come back after all?

It still didn’t feel right. It kind of didn’t make sense for me to try to become a part of the theater bubble in Prague while there’s so much going on in my country. I was in touch with our board member Anton, who I have already known for a long time, and we agreed that it makes sense for me to join Base UA.

How did the idea of specifically helping kids grow inside of you?

It was more about finding and filling the gap.

Which gap?

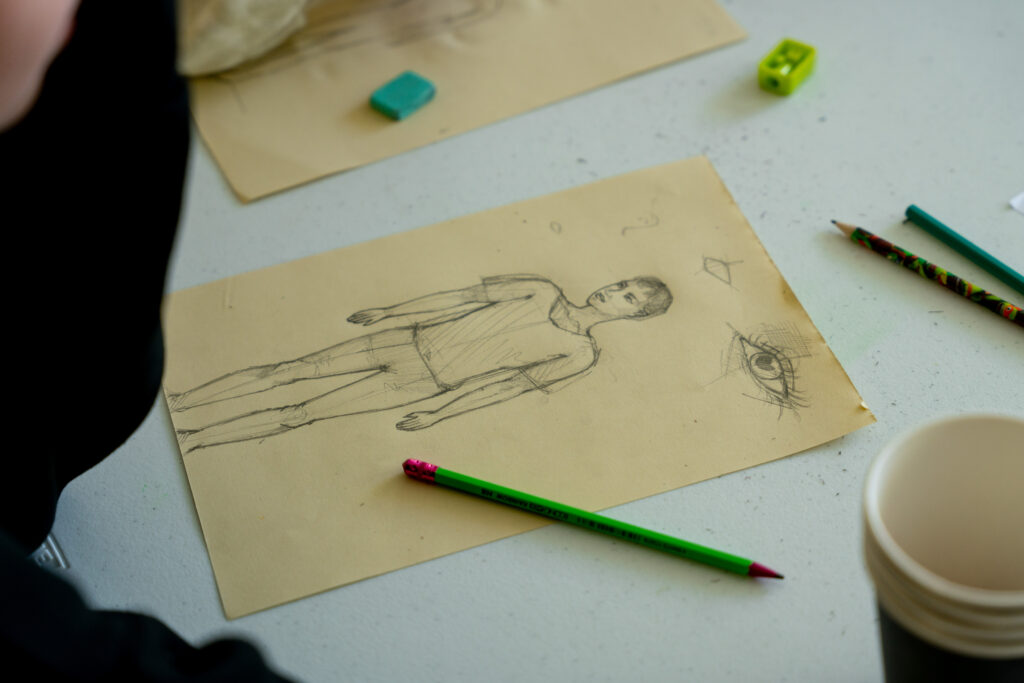

That there was almost no work done for the kids in the sense of cultural and artistic education on the ground. There were the Base-UA-Art-Camps happening, which was super amazing, but those are only for kids who already fled the war. Some of our team members started organizing some small events, for example sculpting. But beyond that, there was no structure. Also, I have a lot of experience working with kids, cause back then in Donetsk I was teaching kids in drawing and painting.

What are your plans for the cultural events on the ground?

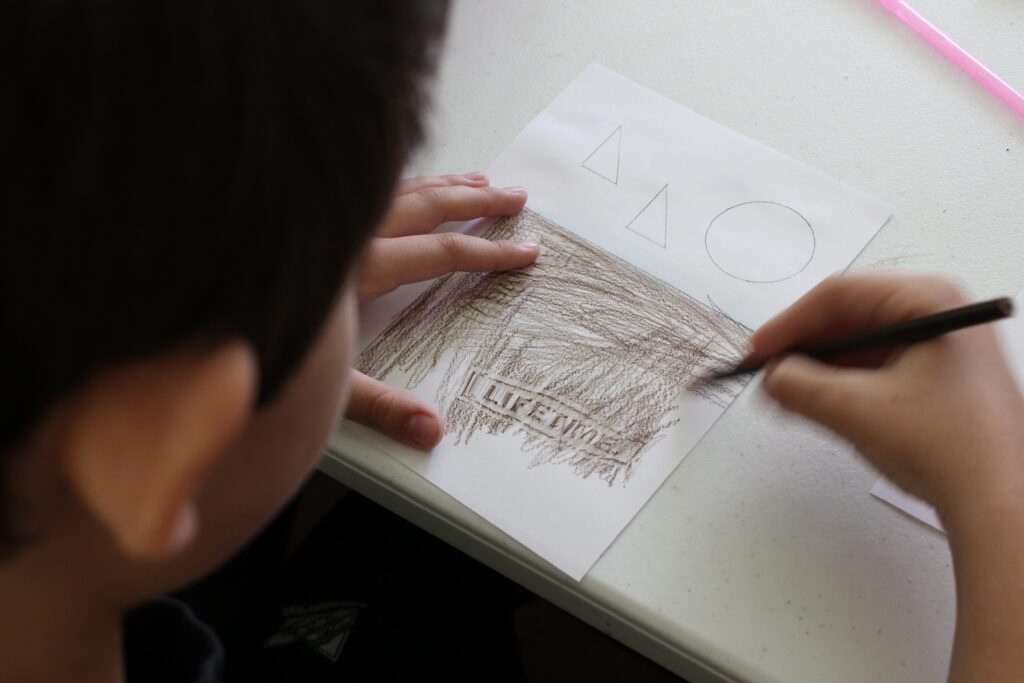

Well, because I have this theater background, I’d really love to emphasize this topic. But sure, this won’t be the only direction we’re going. We already worked a lot on the system of cultural weeks for the kids, concerning fun and exciting science events, painting, drawing and sculpting. We also talked to several teachers and coaches who deal with adolescent development in a sociological way. So we try to really examine the spectrum of growing up in its entirety.

I understood that you traveled through Donetsk region to find out about the needs and the number of children remaining in this environment. Can you give us an approximate count?

We just started this research, but we already did the first part of it. We went through cities and villages in the region for one week, but there is still so much to explore. We visited about ten towns and villages. The most terrifying thing we found out was that there a still about 3,800 kids in Konstiantynivka.

Konstiantynivka, a city that is very close to the embattled area around Bakhmut and Chasiv Yar and is under shelling every day.

Yes, it’s a really dangerous place to be. The fighting is still going on in Bakhmut, but if – and I hope not – but if Bakhmut will be taken, Konstiantynivka will be the next target. So, this research was very important for us for the understanding of what is needed.

In which way?

Every town, every village finds itself in a different situation. So the needs and also the legal way of organizing cultural education and activities for the kids are totally different. In Konstiantynivka it is not possible to gather kids in one place because it would be too dangerous, and we don’t want to risk anything. That’s why we work with humanitarian centers where there are bomb shelters. There we mostly help with providing material. So when the kids come with their parents to pick up humanitarian aid, we use this short period of time. Also, the local volunteers can simply give the material to the families. But in other cities like Kramatorsk it is possible to organize events with a small number of kids where we can dive deeper into several topics.

As you were saying, you already organized events with kids in the last few weeks. How did the children appear to you?

In the first place, it was really tiring. It was hard to give them the attention and energy they needed and were searching for. Working with kids in a peaceful environment is already a hard job because you have to give 100 percent. Knowing that these kids didn’t have a social life for such a long time makes it much more difficult. But then you find out that everything you give returns so quickly. But on the other hand, they need time to build trust.

How do you mean that?

During this war they got used to this kind of volunteers that appear, give them some candy or toys, take photos, and disappear again. But after three days they started to realize that we actually stay. So they started to open up a lot. When we organized a picnic for them on the third day, they started running around, playing games and laughing. Also, some of them started to open up in an emotional way, telling us about their family situation, which obviously is a very tough topic. You can actually see how they missed these social activities and how important this is – also for their social skills. But we’re still not at this point where they really can talk about their feelings and mental state.

How does it feel for you – as a person, who fled the war in 2014 – to work with kids who still suffer from this situation?

I actually never thought about that. There is definitely an understanding of their situation, because I was born and raised in Donetsk. So I can relate to them and they can relate to me. Often, when they find out, they are surprised, because I speak Ukrainian and not Russian. So my history can also be an educational part of these kinds of conversation. I can explain the meaning of Russification specifically in Donetsk region and how the language is connected to this. So I definitely feel like I’m in the right place: I’m here, I’m home, I understand these people, and even if I don’t fully support it, I get, why they don’t leave – because my family also never left. My mom still lives in Donetsk.

Impressions of several cultural events with children on the ground