Tetyanivka is Eugenii’s home. This is where he was born in 1950, where he grew up, where he spent his youth and where he found his love. Tetyanivka is located south-east of Svyatohirsk, in the Donetsk Oblast. The small town of Svyatohirsk was occupied by Russian troops until September 2022. The Siverskyi Donets River, which forms a border between Tetyanivka and Svyatohirsk, separated Ukrainian and Russian-controlled territory at the time. Eugenii’s village was the first line of contact.

Learning about his talent: photography

He knows the people here and they know him. His family is also well established. When Eugenii was a child, they probably had the largest herd of cows in the entire village. 120 of them – spread over three meadows. Their shepherd dog was clever enough to lead the cows from pasture to pasture on his own. It was a wonderful childhood, the 73-year-old remembers today. There is a little melancholy in his voice, yet he can’t show much emotion.

He prefers to talk about the past. For us, too, it’s always exciting to find out how the people we work with lived. How they grew up, how they experienced the transition from the Soviet Union to a free democracy. What they think about the war.

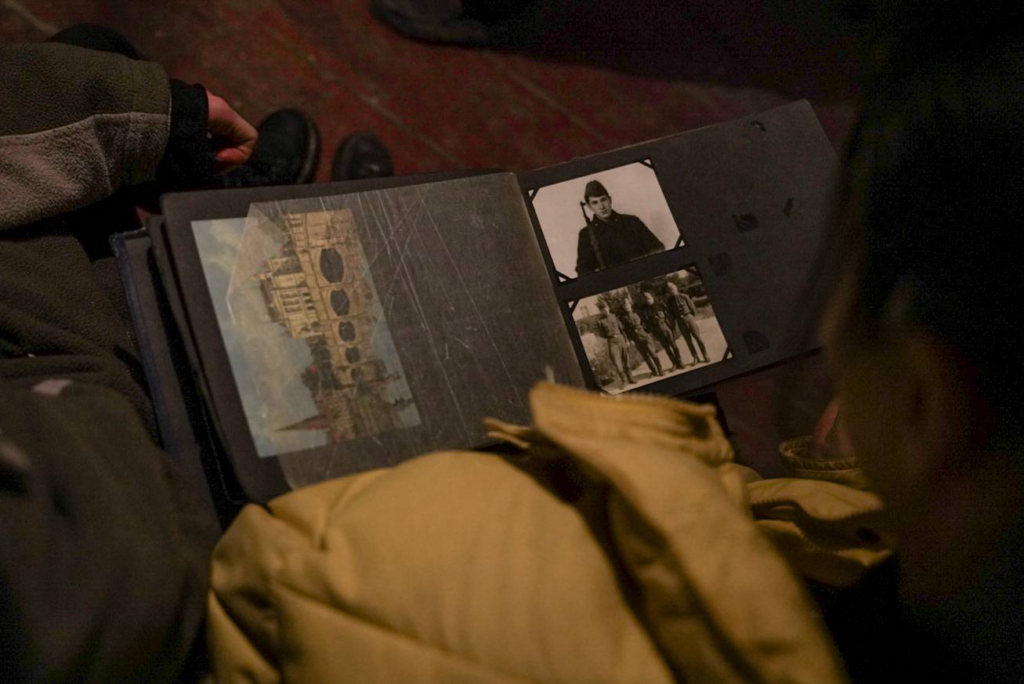

Eugenii answers questions with anecdotes. He walks around the house looking for photos and can tell a story about each one. He started taking photographs in his younger days. He had a Smiena camera, one of the best brands in the Soviet Union back then. And Eugenii loved this new hobby. He learned to develop the photos himself, even when he was serving in the naval fleet in the north of Russia, he took a lot of photos. His commander recognized his talent. He organized a laboratory and got him an even better camera. A Zenit.

He still keeps some of the materials in his house. But where – he doesn’t know. “Ever since artillery hit here, everything has been a mess,” he says.

Eugenii sits on a chair in the middle of his living room. The room is no bigger than 3.5 by 3.5 meters. The chair is covered in paint stains and dust, the screws are coming loose from the backrest. Two of the four walls are still original, dating back to the 1970s. The house was built then, Eugenii bought it in the 1990s. For himself, his wife and his daughters. The two walls have been renovated – the large cracks that were running through the walls two days earlier and the holes have now been plastered over. Compared to the rest of the house, the white paint almost glows. But the two other walls shine even brighter.

House damaged by russian shelling

Base UA first came into contact with Eugenii in October. Back then, there was a large hole in the corner of the two outer walls. He already knew that his house had been damaged when he decided to return to his home from Turkey. But he wanted to return. Base UA came to help him prepare the house for winter. We tore down the walls and built new ones. New insulation, fresh paint. The front door was moved a few centimeters to the left. It’s a bit unusual for him, but he’s always had to adapt to new circumstances. He knows that. Even his father had to deal with new surroundings and new dangers in the past.

“My father was in St. Petersburg, which was Leningrad back then, when the Second World War began,” he says, as the yellow light from a ceiling light shimmers faintly through the dirty fabric of the lampshade. Now and again, muffled explosions can be heard from a distance – the military is demining the area around the formerly occupied territories.

Eugenii tells us that when the German Reich attacked the Soviet Union on a broad front on June 22, 1941, his father was serving on a ship. One day before the war began, Stepanovich, Eugenii’s father, married his wife, Eugenii’s mother. Then he suddenly had to fight – and they were separated. He served throughout the war and had to work for the Soviet Union’s military for another five years.

Two generations of soviet soldiers

Eugenii also had his time in the Soviet military. After school, he had just finished his training as a blacksmith when he was called up for military service. He was also transferred to Russia. He served for two years. “I was in the aviation unit and worked at the military airport, maintaining the planes,” he says. That was in the north of Russia, it was very cold – they usually had to heat the engines of the planes so that they were ready for use.

But he never found this time hard or unpleasant. There was none of the usual harassment of new arrivals in his unit and he even made a lot of friends. After his basic service, Eugenii was transferred to the GDR. At that time, East Germany was also part of the Soviet Union. “We often drank Korn,” he remembers. “It wasn’t as hard as the vodka here, but it was nice.” Only the cigarettes, he says, were too expensive for him.

The fact that the children or grandchildren of his former comrades are probably fighting against his people today has crossed his mind from time to time, he says. He knows that the people who live in Russia are not free. “But I also believe that they have a kind of dirty heart. They have very bad thoughts about us Ukrainians. So their life in a dictatorship cannot be an excuse for what they do to us.”

“My wife almost constantly cried”

When the shelling of Tetyanivka, his home, began in spring 2022, Eugenii and his wife Valentyna were at home. “Our children had already fled to Germany,” he says. They kept telling them that everything was fine. But in reality, they were very scared. “My wife almost constantly cried at first”, says Eugenii.

Then Russia bombed the famous Svyatohirsk monastery. Chaos spread throughout the village – it was very frightening. “When the planes came, it was suddenly as bright as day – in the middle of the night.” He watched the explosion from his bedroom window. “At that moment, we were already thinking about fleeing,” he says today.

But things turned out differently.

He first went there by bike to see the damage with his own eyes. “So many people from my village were there. They were crying. Children were picking up shrapnel, other people ran into their basements and took their mattresses with them.”

But the escape plans evaporated.

Getting used to the danger of war

“We had our garden, our rabbits, the bees – a lot of things we had to take care of,” says Eugenii. Here, in his village, he is at home, he knows his place. “We thought we would get used to it.” And so it was.

“Our military was uphill,” he says, pointing over his shoulder with his thumb. The three-bedroom house is on a hill, halfway up. 300, maybe 400 meters further up, a Ukrainian artillery unit had its base. The Russians were downhill, on the other side of the river. “We saw the rockets flying overhead every day.” He talks about it as if it were written somewhere in a dusty history book. Very calmly. Without fear, without tragedy in his voice. Purely informative. That’s how it was. Back then. A long time ago.

In truth, this memory was only a year ago. When he heard the whistle of the rockets, he would go outside to ask Valentyna to come in. She was mostly outside, he says. To work in the garden, look after the rabbits, feed their dog Filja. “But she always just said: ‘Let me finish this, then I’ll come in’.” They don’t have a basement or any shelter to protect themselves from artillery fire.

In the end, he says, a rocket made the decision for them. A Russian projectile was flying over their garden when it was destroyed by Ukrainian air defenses in mid-air. “The explosion was directly above us,” he says. That was the signal, the alarm bell. Now they wanted to leave.

“We could have been injured or even killed too”

They fled to Turkey and hadn’t been there long when they received the news: Their house had been hit. When he heard about it, he says today, he thought: “We could have been injured or even killed too.” He is therefore glad that the explosion over their house made the decision for them. “Our lives are worth more than our house.”

Eugenii’s wife Valentyna had to move directly from Turkey to Russia to care for her sick mother. Eugenii came back home. His house now has two new walls, some new acrylic windows and a new veranda with a canopy. As for the rest, the 73-year-old wants to do it himself.

Since then, Base UA has already winterized more than five other houses in the village of Tetyanivka and fitted them with new windows. It is precisely the windows that were destroyed by the shelling, as they break due to the pressure wave from nearby explosions. Even if the house itself was not hit.